Tired of boring, flat graphics? I mean, what can you do with them? They loll about on the screen, static and still, conveying their limited scope. Sure a good figure might be worth a thousand words, but after that it just sits there. Lifeless. For many types of technical illustrations, that’s where the journey ends. That’s also where the value they add to your technical communications content ends. However, for the select few, a new frontier awaits in the world of 3D graphics.

Tired of boring, flat graphics? I mean, what can you do with them? They loll about on the screen, static and still, conveying their limited scope. Sure a good figure might be worth a thousand words, but after that it just sits there. Lifeless. For many types of technical illustrations, that’s where the journey ends. That’s also where the value they add to your technical communications content ends. However, for the select few, a new frontier awaits in the world of 3D graphics.

The world of 3D graphics is pretty big, spanning everything from technical communications to video game environments. In this article, I’ll focus on technical illustrations to support hardware documentation: service procedures, spare parts, and so forth. The 3D graphics I’ll describe grow out of the world of computer-aided design (CAD). Companies use CAD software to design their products, and as part of that process they develop a 3D model of the product. The cool thing about this model is that it’s 3D and it’s built out of all the components that are used to manufacture the product. In general, everything down to the nuts and bolts used to put the thing together are in the model as independent pieces. The 3D CAD model is like a jigsaw puzzle. It consists of a multitude of independent pieces and parts, but it appears as the complete product in the model.

So what makes 3D graphics special? The key is interactivity. These graphics aren’t passive; you can play with them. 3D graphics often have viewers that enable you manipulate the graphic in many different ways. These viewers can be integrated into authoring applications to let writers interact with the graphics. The viewers can also be integrated into web browsers as plug-ins, so you can use them in HTML documentation. That gives users the opportunity to join in the fun.

What Sorts of Things Can You Do with 3D Graphics?

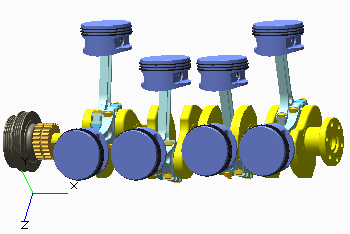

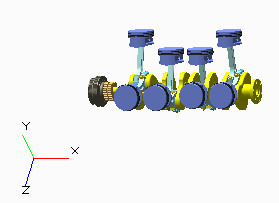

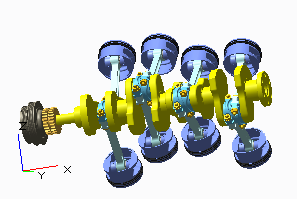

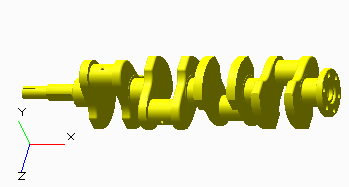

Well, here’s a 3D graphic of a crankshaft.

You can make it smaller.

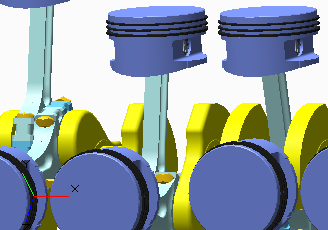

You can make it bigger.

You can move it around and spin it about to look at all the aspects.

You can select one or more of the parts that make up the crankshaft and just look at that part.

Those are just a few of the ways you can interact with the graphic. For authors, if you want to deliver old-fashioned 2D graphics for print or PDF, this means you can play with the graphic in the viewer until it’s how you like it and then convert that view of the graphic into a .jpeg or .png or whatever you need. You can do that as many times as necessary to graphically document all the required aspects of the product. But the fun doesn’t stop there.

Yes, the level of interactivity can go much deeper than that. In fact, there are several more tricks 3D graphics let you perform. First off, a 3D model actually consists of a lot of different files munged together into a sort of zip file. You can store different things inside of it to use later. One thing you can store is different views of the model. You can have a default view for the most used version. Then, you can define several other versions of the model and store those inside of it too. You can have views of different aspects of the model, views that contain just a few of the parts, views that are close ups of different components, and so forth. The viewer for a 3D graphic often has a control that lets you select from these predefined views.

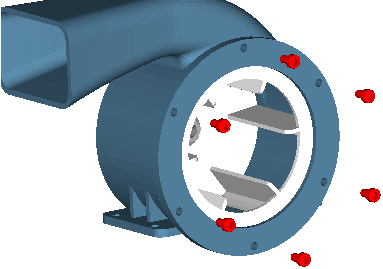

Another thing you can store in the model is animations. Let’s say you’re developing a repair procedure for a blower. You want to demonstrate the bolts that need to be removed from the blower to service the flange. Well, since all of those parts exist independently inside of the 3D graphic, you can develop an animation that highlights all of those bolts and shows them being removed from the flange.

The blower graphic contains independent graphics, such as the bolts, that make up the whole model.

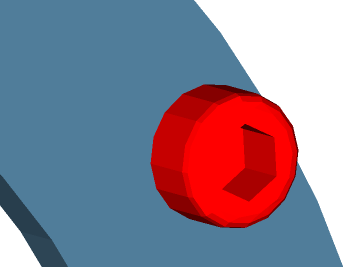

Once you have stuff like views and animations in a 3D model, then that opens the door to all kinds of fun linking possibilities. Links from HTML text can trigger actions in a 3D graphic. You can create a link that changes the display of the graphic to one of the predefined views stored in the model or a link that triggers an animation. You can make a link that zooms the view of the graphic to a specific part, a link that highlights a part of the graphic, or even a link that both zooms the view to a specific part and highlights it as well. Here’s the result of a link that zoomed the view of the blower 3D graphic to one of the individual bolts and highlighted that bolt in red:

Using links, you can build interactivity that zooms into an individual bolt.

You can even attach links to individual objects in a 3D graphic. Since each object in the model exists independently, each object can be the source of a link. These are sometimes called hot spots. For example, in the blower model the flange could be the source of a link. In this case, when somebody clicked on the flange in the 3D graphic viewer that would activate the link and jump from the graphic to something like the procedure for removing the flange.

Practical Applications for 3D Graphics in Technical Communications

Practical applications for 3D graphics obviously include installation and repair procedures. Imagine if the repairman coming to fix your washing machine was toting his tough tablet or laptop and had 3D graphics integrated into the documentation for servicing the product. He could look at the model of the machine, see all of the parts, and know exactly what he was dealing with before pulling out the first tool. Repair procedures could include links that trigger animations in the model demonstrating exactly what needs to be done. It opens up a whole new world of possibilities.

Supporting sourcing of spare parts is another way to apply 3D graphics in technical communications. When the door glass for my washing machine cracked, I went to the company’s website and tried in vain to figure out what part I needed to replace the glass. I managed to find a 2D graphic for my washing machine, but I couldn’t make it bigger and it was really unclear what part number I needed. I called the company and their rep had no better luck figuring it out. Suppose that instead I’d been able to view a 3D model of the washing machine. In this case, I’d be able to move the model around, zoom in on the door, and select the exact part I needed to replace. Taking it a step further, what if the object in the model was linked to a row in a parts table below the graphic so that when I clicked the part in the model it jumped to the row in the table for that part. It could even work in reverse where a link in the parts table row highlighted the corresponding part in the 3D graphic. That sure would have made my life easier. Imagine how useful this kind of technical communications content would be for hundreds or thousands of your your users.

So how can you start using 3D graphics in your technical communications work? Most of the CAD-related ones like I covered here are developed using proprietary formats. The examples here were produced using the Creo and Arbortext IsoDraw products from Parametric Technologies Corporation (PTC). Disclaimer: I’m employed by PTC, though I’m not acting as their representative here. Other CAD solutions provide similar models, such as TurboCad, Punch!Cad, AutoCad by AutoDesk, and SolidWorks. Outside of the proprietary area, Computer Graphics Metafile (CGM) graphics offer some of the capabilities of 3D graphics. While CGM graphics aren’t 3D models, they do offer some of the same interactivity potential. The WebCGM variant in particular offers similar possibilities.

Both 3D graphics and interactive 2D graphics have an increasing role to play in producing technical communications content that engages and educates consumers of your products. An engaged customer is most likely a repeat customer, and that’s a technical communications spin on your company’s bottom-line that everyone can appreciate.