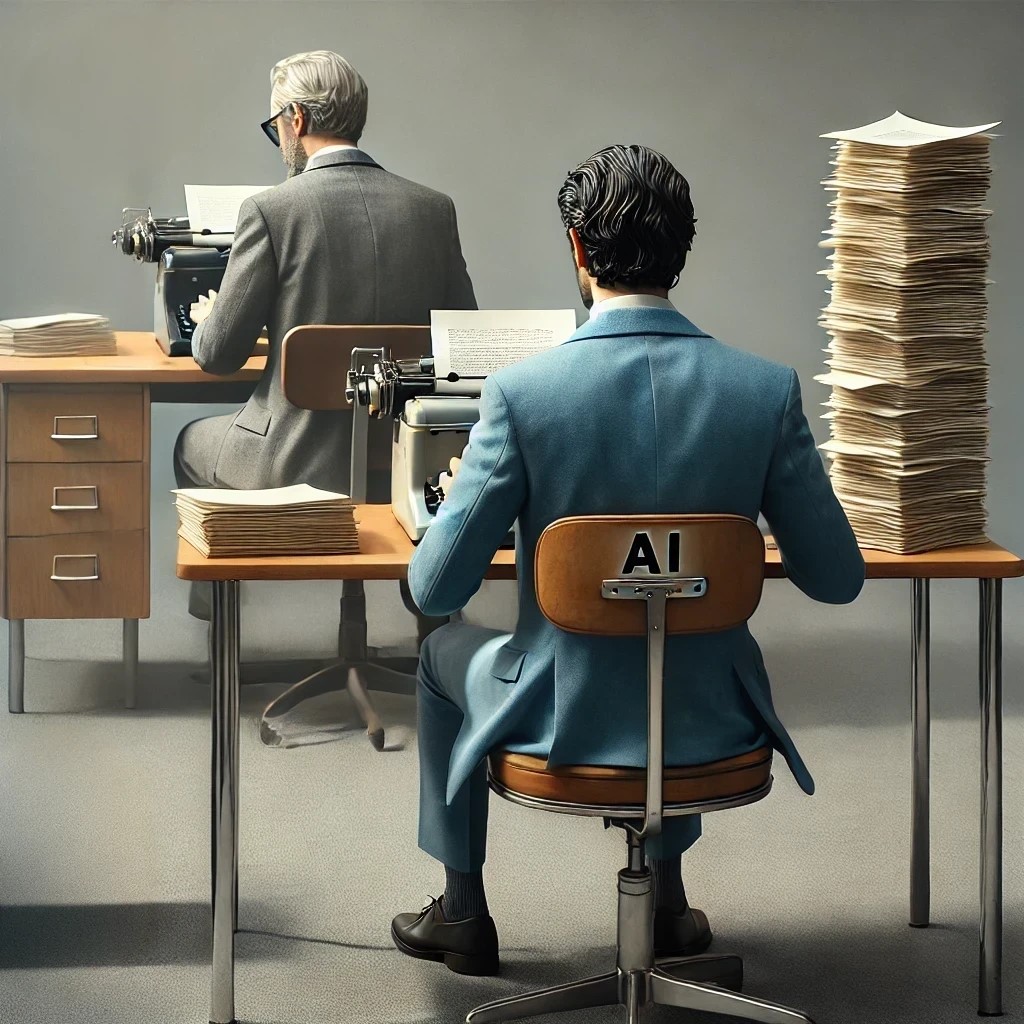

Image by Chris Farmer, generated by AI

This recent interview between Erika Konrad, of NAU and student Chris Farmer, goes in depth into the world of AI contributors and training.

Chris, I understand that you are an AI trainer. What does that mean?

AI Contributor might be more accurate; I provide data that is used in AI training. I’m definitely not a software engineer! That said, I’ve participated in several projects that are making AI better. I spend approximately fifteen hours per week working as a freelance contractor, delivering data used for RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback).

Different skill-sets are required depending on the project. My background and education places me in the category of a “generalist.” Most liberal arts majors will find themselves in this category, which requires good critical thinking and the ability to process information across a variety of fields. The other categories are STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math) and Coders. Generalists might work on STEM tasks, but often those tasks require more advanced knowledge; examples can include solving complex calculus equations or physics problems like calculating the distance traveled by a particle. Coders have knowledge of programming languages, and they evaluate prompts asking the model to explain everything from creating lines of code in Python to understanding function parameters in TypeScript—please don’t ask me to explain what that means because I can’t!

I get shifted around a lot based on customer needs, but examples of projects I’ve worked on include reviewing the quality of AI outputs, grading outputs against each other and justifying my preferences, crafting ideal responses for user generated prompts, and writing prompts designed to push the model’s limits—sometimes including an ideal response for those as well. Other projects involve identifying the explicit and implicit requirements to fulfill prompts and creating lists of those requirements for models to learn from. Prompts are the requests or instructions given to the AI. Prompts might give the model specific task directions, like summarizing a lengthy essay using a certain number of words or formatting data in a specific way, or they might give the model a role to play—like a comedian with the personality of Edgar Allan Poe. You’ll hear some interesting stories from that persona…

I’ve also served as a reviewer, verifying and editing the work of others, and as an auditor performing QA checks on data prior to its delivery to customers. I get shifted around a lot based on the needs of the company I’m freelancing for.

What are you learning from your AI training work that relates to technical and professional writing?

It has really improved my attention to detail and my research skills. There’s little tolerance for grammatical errors, because we must provide quality data for models to learn from. So, that requires meticulous attention to detail. I also research outputs across a variety of topics, and that can mean exposure to subjects with which I’m not familiar. Processing large volumes of information and conducting research to understand content across a variety of domains, all within a limited timeframe—I’m on the clock after all—seems like a skill-set that can benefit any writer.

I’m also learning to appreciate conciseness. A response with too much verbosity can be as bad as an overly short—and therefore uninformative—response. Additionally, viewing responses side-by-side builds a keen awareness of consistency. Responses that use similarly structured headings, boldface formatting (not too much), and don’t needlessly shift between ordered and unordered lists, tend to be easier to read than responses that ignore these factors.

Improved context and time savings also contribute to AI advantages

I think AI can be a timesaver for writers. You have to validate its outputs (at least for now…), but that can be easier than researching data from scratch. Especially if you ask it to provide references for its statements—it might lead you to a source you wouldn’t have otherwise discovered. That said, don’t assume that the references it gives will contain the information it provided—or that they will even exist. Test every link, and be wary of data that you can’t locate. The information might still be correct, even when the model provides hallucinated references, but it’s always up to you as a writer to validate your sources.

AI can also aid in understanding content. If writers find themselves generating content related to a field in which they have limited expertise, AI can help them build a baseline understanding of the topic, and it’s good at summarizing data and converting complex jargon into clear language. For example, I recently took an elective called Rhetoric and Writing in Professional Communities, and the coursework involved reading Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge, a very “heavy” philosophical book about knowledge and discourse. After reading passages and forming an understanding of the content, I asked AI to analyze the data. Sometimes, it reconfirmed my interpretation. Sometimes, it gave an output that I dismissed as completely wrong. And sometimes, it led me to view the data differently and acquire an insight that I wouldn’t have formed on my own. I think that’s an area where AI has the potential to help people grow.

When I read something, I form an understanding of the content based on my unique perspective and experiences. I might study an analysis from another individual and learn from their perspective, but I only have so much time. AI can process tremendous amounts of information, and it can output one or several interpretations of the content based on all the information it processes. People might argue that those AI outputs can be incorrect, but so too can the outputs that people produce. AI makes mistakes, and you need to verify what it’s saying (again, for now…). But it can help writers understand content, and it can process substantial amounts of data quickly.

What challenges are you finding in AI training work?

I think I’ve mentioned the biggest one a few times, and that’s accuracy. The models are only as good as the data they’re trained on, and the internet often contains data that at best is partially correct and at worst is completely incorrect. AI can process a lot of information, and it’s gotten good at understanding the patterns of our language enough to predict the next word, phrase, or paragraph that it should present to us based on our inputs, but we have to question its outputs as much as—if not more than—we question any other information we come across. I recommend viewing AI as a source similar to Wikipedia; it’s probably correct, it can improve our understanding of a variety of topics, and it can help us find additional references, but I wouldn’t consider it a scholarly source, and I wouldn’t cite it in any formal document.

One recent example involves completions I was grading from a model. The initial prompt asked what “mission command” was. The model gave an answer, and then the user asked about how the Army defines the “principles of mission command.” The model output a response listing the “six” principles of mission command. I validated the response, and my initial web search showed multiple websites that list those six principles. However, as I scanned the search results, one caught my eye that mentioned seven principles. This article led me to Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-0, where I learned that there were indeed seven principles. Only a few outputs produced by the model gave the correct answer. Of course, I graded the correct answers as the preferred responses, so hopefully the model will stop making that error when my training data is uploaded, but this is an example of where the model is only as good as its data.

Of course, given that there were many online articles giving answers that were not fully correct, a human might have made this mistake too, but a human is also more likely to find the correct answer in the haystack of misinformation that is the internet (repeating myself again when I say: for now…)

I feel that some professional and technical writers are panicking about AI and that some managers are jumping on the AI bandwagon just because it is the latest “thing.” What are your insights about that?

I agree that managers are “jumping on the AI bandwagon,” at least from what I’ve seen. My wife generates online content for a company, and she’s been instructed to shift from creating all of her own content to editing AI generated content. She is still producing quality work, but AI is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. My understanding is that the company she works for had to shift to using AI in order to keep up with competitors who were producing more content at a faster rate. This illustrates the pressure managers are under; if companies don’t learn to leverage AI, they risk being left behind by those that do.

I have to add a disclaimer here that aside from my wife’s situation, my experience with this is limited. I’ve read a lot of articles discussing the subject, and two themes appear often:

- Businesses shouldn’t use AI just for the sake of using AI, but they should explore how it might solve specific problems.

- Many businesses already have AI projects underway, and those that don’t may need to evolve to keep up.

The same goes for professional and technical writers. They still have an important role, but they need to learn to use the new technology, or they may be left behind by those that do. The best thing writers can do now is to practice with AI—learn to craft prompts that produce desired outputs. I said earlier that AI is only as good as the data that goes into it, but this isn’t 100% true. AI is also only as good as the quality of the prompt. Sure, simple tasks can be carried out with simple prompts. But crafting detailed prompts that produce quality outputs again and again is its own art, and I suspect that in the future, some of the best writers will also be adept prompt engineers.

How did you get started working with AI?

A lot of companies currently advertise jobs for AI trainers. I received a communication from a recruiter through Handshake, a job site geared toward students, that I joined through my university. The easiest way to find companies that are hiring is to search for “AI training jobs” or “RLHF jobs” online. Of course, there’s a lot of competition for remote jobs, and you need to research any company you are considering. I definitely recommend doing a Reddit search for the company name and reviewing comments—with an understanding that people often only write about a business when they have something negative to say, so the view may be skewed. Still, it’s worth reviewing the data. Unfortunately, not every job advertised online is legitimate, so be careful if you pursue any remote job. Fortunately, my experience has been positive!

Christopher Farmer has served in the US Navy for 25 years and is pursuing a MA in Professional Writing from Northern Arizona University. He has a background that includes managing teams and working with technology, and he is a Certified Postsecondary Instructor (CPI). He has also earned a BA in English from Thomas Edison State University and a BS in Liberal Arts from Excelsior University.